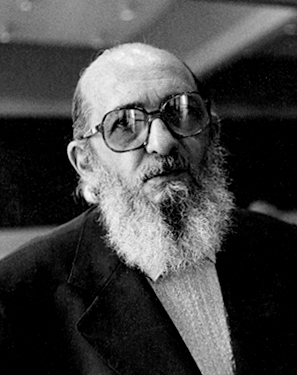

Paulo Friere: Educator, Theorist and Christian Socialist (1921-1997)

Writing in relation to the Brazilian people, Freire contended that “They could be helped to learn democracy through the exercise of democracy; for that knowledge, above all others, can only be assimilated experientially” (1973:36). Given the transition of Brazil from a closed to an open society at the time, Freire said in Education for critical consciousness:

“I was concerned to take advantage of that climate to attempt to rid our education of its wordiness, its lack of faith in the student and his [sic] power to discuss, to work, to create. Democracy and democratic education are founded on faith in men [sic], on the belief that they not only can but should discuss the problems of their country, of their continent, their world, their work, the problems of democracy itself. Education is an act of love, and thus an act of courage. It cannot fear the analysis of reality or, under pain of revealing itself as a farce, avoid creative discussion” (1973:36).

The value of Freire’s work lies in his linking micro-educational methodologies to theories of social change. This understanding, combined with his emphasis on te integrative processes of action, critical reflection, theoretical knowledge and participatory democracy, support the contention that the micro-macro dichotomy i a fallacious one. While the underlying assumption of Freire’s work is that critical understanding would lead to critical action, there is the possibility that his emphasis on egalitarian educator-learner relationships, and action and reflection, could become ends in themselves. However, as elucidated in my biography, Freire’s work had a profound impact on educational and political epistemologies in South Africa during the 1970s and 1980s. His writings provided the philosophical and methodological foundations for the positive engagement of students and of wider citizenship groups in the processes toward the struggle for democracy.

Central to Freirian pedagogy are dialogue and praxis – reflection in and on action – that take place in what Freire called cultural circles, where cultural animators/facilitators engage people in informal settings in small groups (Freire, 1973; Escobar and Escobar, 1981). In such settings all participants are educators and learners; the facilitator does not transmit or distribute knowledge as an objective intellectual or neutral expert. The cultural animator/facilitator engages with people so that all can understand a given reality. The animator’s role is primarily a political one where the dialogue is designed to uncover social realities, and to awaken critical consciousness aimed at transformation of a repressed and repressive society.

One way of achieving this is the use of generative words, codification and decodification (Freire, 1973; Escobar and Escobar, 1981). Groups choose generative words, which may be linked to pictures, photographs, sounds, the environment, etc, also called political alphebetization, for their sociological and political salience to critically describe and analyze situations that they find themselves in. Codification is “the intellectual representation of an existential situation” (Escobar and Escobar, 1981, p. 5) i.e. the meanings and concepts linked to the generative words. E.g. “race” might be the generative word, and the codification might include the overt and nuanced aspects of race; verbal and non-verbal dimensions; and visible and non-visible manifestations, to analyze the deep structures (e.g. of race and race thinking) within that which is tangible and visible – e.g. policies, laws, living conditions of people influenced by racism. Decodification involves a critical engagement with alphebitization and codification to engender critical consciousness, reconstruction and social change. The praxis supports making learning a part of the process of social change itself.

According to Freire (1973) “Dialogue requires social and political responsibility, it requires at least a minimum of transitive consciousness” (p. 21), which is paramount as Freire warned about the dangers of naïve consciousness, which can manifest in things like fanaticism, nostalgia or fatalism. In the words of Freire (1973):

A critically transitive consciousness is characterized by depth in the interpretation of problems; by the substitution of causal principles for magical explanations; by testing of one’s ‘findings’ and by openness to revision; by the attempt to avoid distortion when perceiving problems and to avoid preconceived notions when analyzing them; by refusing to transfer responsibility; by rejecting passive positions; by soundness of argumentation; by the practice of dialogue rather than polemics; by receptivity to the new for reasons beyond novelty and by the good sense not to reject the old just because it is old – by accepting what is valid in both old and new (p. 14).

Underscoring Friere’s (1973) approach is the importance of finding “solutions with the people and never for them or imposed upon them”, where people “enter the historical process critically” enabling them to reflect on themselves, their responsibilities and their roles; “indeed to reflect on the very power of reflection” (p. 13, highlights in original), which would increase their capacity to choose. These must be academia’s approach in our work with students, and social workers’ approach as they work with people in diverse settings.

Film about Friere: