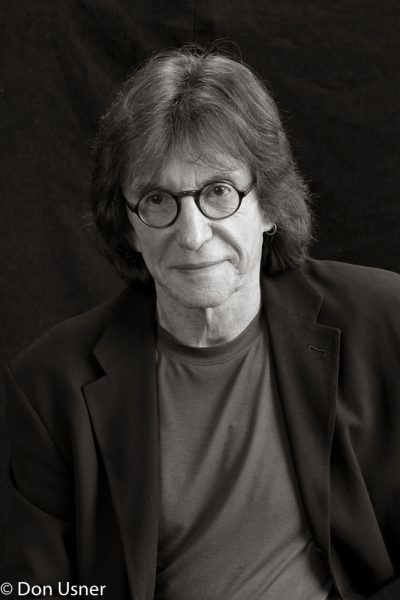

Henry Giroux: Scholar and Founding Theorist of Cultural Pedagogy (b. 1943 -)

Giroux embraces the central theses of Freire (1970, 1972, 1973) and Gramsci (1988, 1971, 1977) regarding politics, culture, class, education, critical consciousness and critical action, but he adds to his radical pedagogy significant issues of “race”, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, multiculturalism, citizenship education and identity politics. Given social work’s current preoccupation with multiculturalism, Giroux’s views are worth mentioning. In what he called an insurgent multiculturalism, Giroux (1994, 1997) called for discourses on multiculturalism which have been used to victimize minority groups, with an emphasis on their deficits and one which presents them as the “other”, to be combined with discourses on power, racialized identities and class. In doing so, we need to move away from using white, which is a mark of racial and gender privilege, as a point of departure in identifying difference. Whiteness, as a “race” and colour, represents itself as an archetype for being civilized and good, and in so doing represents the Other as primitive and bad. This is characterized by the textured use of colour in the English language as a signifier for such archetypes. Thus all that is bad has become associated with black, such as black book, black sheep, blacklisted and blackmail. Would a deconstruction of “race” from the constraints of such representations mean a deconstruction of the very language that reproduces it; a language that has become embedded in the psyches of people to become, in Gramsci’s terms, the common sense?

Citing James Baldwin, Giroux claims that “…differences in power and privilege authorize who speaks, how fully, under what conditions, against what issues, for whom, and with what degree of consistent, institutionalized support” (1997:236). Critical multiculturalism must examine how racism in its various forms gets reproduced historically and institutionally, and essentialist views regarding black, female or African must be rejected. While multiculturalism generally focuses on the other, Giroux calls for a multiculturalism that provides “…dominant groups with the knowledge and histories to examine, acknowledge, and unlearn their own privilege” and to “…[deconstruct] the centres of colonial power and [undo] the master narratives of racism” (1997:236, emphasis mine). An insurgent multiculturalism brings into question not only the effects of racism in terms of the nihilism that permeates black communities and of poverty, unemployment, racist policing and so on, but the origins of racism in the historical, political, social and cultural dynamics of white supremacy. This proved to be invaluable in my engagement and reflection with the students.

Giroux (1997) contends that Gramsci’s thesis regarding ideological hegemony, as a form of control that manipulated consciousness and shaped daily experiences and behaviour, is crucial to our understanding of how cultural hegemony is used to reproduce economic and political power. Advanced industrialized countries like the United States distribute not only goods and services unequally, but varying forms of cultural capital – “…that system of meanings, abilities, language forms, and tastes that are directly and indirectly defined by dominant groups as socially legitimate” (Apple, cited in Giroux, 1997:6). Within the dominant culture, meaning becomes universalized, and historically conditioned processes and notions of social reality appear as self- evident, given and fixed. Thus, as Freire (1970, 1972, 1973) and Gramsci (1971, 1977) held, the importance of “…critical reflection lays bare the historically and socially sedimented values at work in the construction of knowledge, social relations and material practices” (Giroux, 1983:154).

Giroux contends that the modes of analysis in radical pedagogy must be underscored by two major questions: (a) how do we make education meaningful by making it critical; and (b) how do we make it critical so as to make it emancipatory (1983:3). Giroux (1983, 1997) attacks modernist, technical-positivist rationality, which elevates reason to an ontological status, arguing that it does not allow for subjectivity and critical thinking, and that it is antithetical to the development of citizenship education. He posits arguments for citizenship education to be informed by an emancipatory rationality, which is based on the principles of critique and action, and which reproduces and stresses the “…importance of social relationships in which men and women are treated as ends and not means” (Giroux, 1983:191).

Emancipatory citizenship education must be used to stimulate students’ passions and imaginations, so that they may be encouraged to challenge the social, political and economic forces that impact upon the lives of people; to display what Giroux (1983:201) called civic courage. Issues regarding citizenship and democracy cannot be addressed within the restrictive language of markets, profit, individualism, competition and choice, which create indifference to inequality, hunger, deprivation, exploitation and suffering. Educators must have moral courage and power of criticism, and must not, in the name of objectivity, distance themselves from power relations that exclude, oppress, subjugate, exploit and diminish other human beings. We need to create opportunities for the development of critical consciousness and, where possible, for transformative action. In striving to achieve these objectives we need to begin where the students are, within their historical and socio- cultural spaces, in the hope that students would transfer these into their practice contexts.