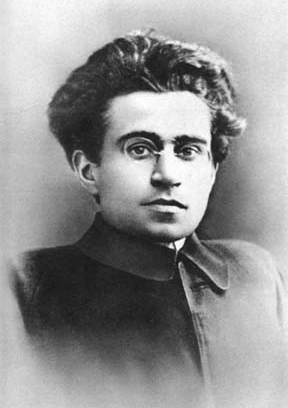

Antonio Gramsci: Philosopher and Politician (1891-1937)

Similar to the thesis of Freire (1972, 1973), Gramsci (1977) argued that education should be used for the creation of a vision of the future through its daily practice, and that knowledge consists of theory and existential experience which is located historically within its context, and is based on action and reflection. Gramsci (1971, 1977) used the concept of hegemony as a central explanation of the functioning of the capitalist system, and elucidated the role of ideology and the state in the reproduction of class relations and in preventing the development of working-class consciousness. Gramsci went beyond Marxist economic determinism by expounding the ways in which common sense and identities are formed within their historical and social locations.

Central to Gramsci’s work is what he called common sense (also contradictory consciousness) and good sense. Gramsci claimed that “…all men [sic] are ‘philosophers’” (1971:323), with their philosophy contained in: (a) language, (b) “common sense” and “good sense”, and (c) the entire system of beliefs, superstitions, opinions and ways of seeing things and acting, which are collectively referred to as “folklore”. However, he contended that common sense functioned without benefit of critical interrogation. Common sense consists of the incoherent set of generally held assumptions and beliefs common to any given society, while good sense means practical, empirical common sense, thus the need to transform common sense into good sense. Contradictory consciousness or common sense is characterized by a dual conception of the world: “…one affirmed in words and the other displayed in effective action” (Gramsci, 1971:326). Thus, ideology is located not only at the level of language but also in lived experience. Gramsci saw the contrast between thought and action to be an expression of profounder contrasts of a socio-historical order. While social groups have their own conceptions of the world, such groups “…for reasons of submission and intellectual subordination” (Gramsci, 1971:237) have also adopted a conception which is not its own. In ordinary times, when such groups are not acting autonomously, it is the conception of the dominant group that prevails.

For Gramcsi (1971) the contradictory state of consciousness, characterized by innocuous ideologies, did not provide for choice and action, but for “moral and political passivity” (1971:333). Thus, in his Prison letters Gramsci wrote, “The outbreak of the World War has shown how ably the ruling classes and groups know how to exploit these apparently innocuous ideologies in order to set in motion the waves of public opinion” (1988:171). However, as Giroux pointed out, contradictory consciousness does not only point to domination and confusion, but also to “…a sphere of contradictions and tensions that is pregnant with possibilities for radical change” (1983:152).

Gramsci (1971) argued that innovation could not come from the masses, at least not at the beginning, except through mediation of the “elite” or the “intellectual”. The role of ideology becomes critical to the extent that it has the potential to reveal truths by deconstructing historically conditioned social forces, or it could reinforce the concealing function of common sense. It is thus vital that common sense be subject to critical interrogation. In Gramsci’s words: “Critical understanding of self takes place … through a struggle of political ‘hegemonies’ and of opposing directions.…Consciousness of being part of a particular hegemonic force (that is political consciousness) is the first stage towards a further progressive self-consciousness” (1971:333). Thus, the theory-practice nexus that arises with ideological critique and critical understanding is not merely a mechanical fact; it reflects the need for a historical consciousness. Historical consciousness, as a moment of ideological critique, functions “…to perceive the past in a way that [makes] the present visible as a revolutionary moment” (Buck-Morss cited in Giroux, 1997:84). Political revolutionary action for Gramsci (1971) could take the forms of war – a war of movement, a war of position and underground warfare. The war of position would constitute the passive revolution that takes place in societies characterized by relative stability.